The obligation to adopt national implementation measures

No state party is known to have adopted new national implementing measures in its domestic law in 2024 to give effect to the core prohibitions of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). Only states parties Ireland and Niue have thus far adopted national legislation specific to the TPNW, while some states parties are in the process of developing such a law. Most other states parties, however, had in place existing legislation that addresses at least some of the obligations under the TPNW before adhering to the Treaty.

While national laws prohibiting nuclear weapons-related activities are present in many states parties to the TPNW, only two so far (Ireland and Niue – see below) have laws explicitly covering all the prohibitions in Article 1 of the treaty, applies these to all natural and legal persons under their jurisdiction, and defines the penal sanctions for violating these prohibitions.

Ireland and Niue have adopted national legislation specifically to implement the TPNW. Ireland adopted its Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons Act in 2019. The list of offences in Section 2 of the Act reflects Article 1(1) of the TPNW and an offence may be committed by both an individual and a company.

Niue adopted its Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons Act in 2021. The Act is explicitly aimed at giving effect to the TPNW. The law defines ‘nuclear explosive device’ as an explosive device ‘whose harmful effects result primarily from uncontrolled nuclear chain reactions’ and a nuclear weapon is a weaponised nuclear explosive device. The prohibitions in Article 1 of the TPNW are effectively implemented in Section 6 of the Law, including the prohibitions on assistance or encouragement. Assistance is defined as aiding or abetting prohibited conduct, while encouraging pertains to urging, demanding, or inciting prohibited conduct where the person has influence over whether that conduct will actually occur.

For more information, see the 2024 edition of the Nuclear Weapons Ban Monitor.

ARTICLE 5 - INTERPRETATION

- Article 5 of the TPNW obligates every state party to take ‘the necessary measures’ to implement its obligations under the Treaty.

- Paragraph 2 of Article 5 stipulates that the duty to implement the Treaty nationally includes the taking of ‘all appropriate legal, administrative and other measures, including the imposition of penal sanctions, to prevent and suppress’ any prohibited activity. It concerns any such prohibited activity whether it is undertaken by natural or legal persons under its jurisdiction or control or on territory under its jurisdiction or control.

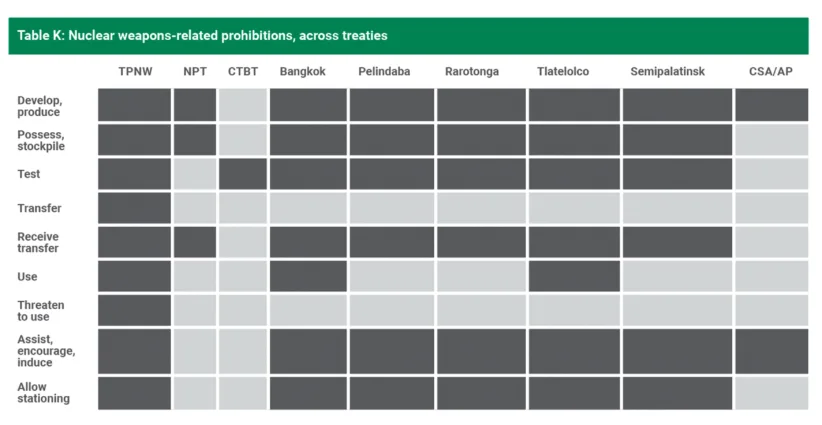

- Appropriate criminal legislation should cover at the least all of the core prohibitions set forth in Article 1 of the Treaty.

- The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has developed and published a model law for common-law states which can serve as a valuable basis for states parties to the TPNW to draft and enact such legislation (at: http://bit.ly/3faEDXV).

- The CTBT and the CWC also require national implementation measures, but there is no such obligation in the NPT or the NWFZ treaties.